GRP Estuary Cruiser

The Boat

I was looking for my ideal cruising boat, but that meant ideal for me. My ideal might not be everyone else’s idea of ideal. Anyone building their own craft has the opportunity to possess the most perfect boat afloat - for them. It is possible to have an historic craft like Joshua Slocum’s Spray or to imitate top-quality cruising craft from well-known brands, or maybe have the best-known racer of the day. What follows is an outline of the thinking and planning that goes on behind designing a one-off boat, tailor-made for a particular purpose. It is a blend of looking back at sailing history, at other boats, picking up good ideas, learning about how boats work, reading about sailing, finding materials and equipment, experience, choices about appearance and making decisions about what to include and what to leave out..

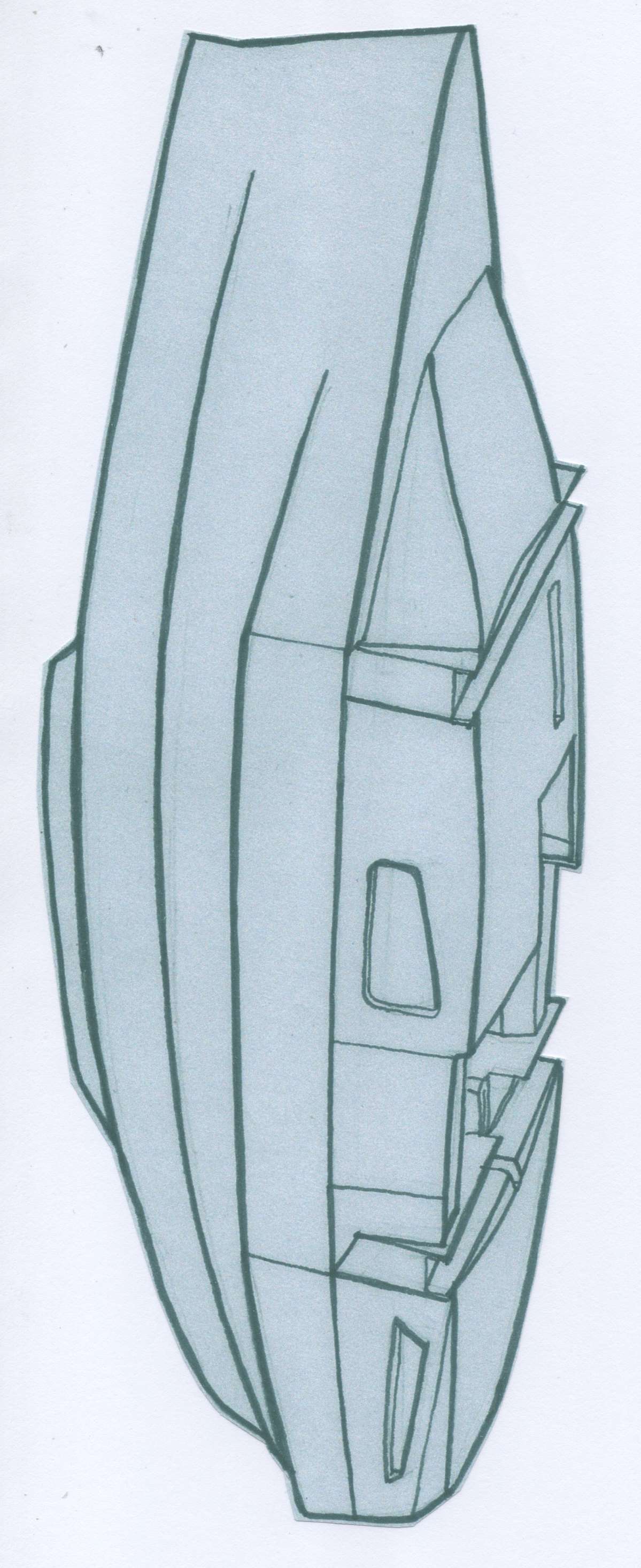

A special boat Below. An early sketch

I wanted another trimaran. I say ‘another,’ because I already had my 35ft offshore-cruising trimaran which was engaged in sailing around Britain; a voyage account that is recorded in the Serial Starship book on this website. This journey was a four-year project which took up much planning and organisation, but left me without a boat at home for lengthy periods. I had been on a previous voyage in Starship to Norway, Sweden and Denmark and I had been impressed with the quality of the sailing area over there, but I rarely saw a British boat. I could understand from my experiences that the logistics of getting a boat there, crewing it and then completing the return journey, was enough to put most people off the challenge. What was needed was a trailer-sailer, to be taken to a ship, transported across and assembled. It could be sailed for the season and then brought back. I was not thinking about a sailing dinghy, but a small cruiser. This was in the days before such multihull craft were generally commercially available.

already had my 35ft offshore-cruising trimaran which was engaged in sailing around Britain; a voyage account that is recorded in the Serial Starship book on this website. This journey was a four-year project which took up much planning and organisation, but left me without a boat at home for lengthy periods. I had been on a previous voyage in Starship to Norway, Sweden and Denmark and I had been impressed with the quality of the sailing area over there, but I rarely saw a British boat. I could understand from my experiences that the logistics of getting a boat there, crewing it and then completing the return journey, was enough to put most people off the challenge. What was needed was a trailer-sailer, to be taken to a ship, transported across and assembled. It could be sailed for the season and then brought back. I was not thinking about a sailing dinghy, but a small cruiser. This was in the days before such multihull craft were generally commercially available.

To make it trailer-able immediately set limits on what could be constructed. Road restrictions would impose a limit of about 8ft (2440mm) in width and the weight had to be restricted, meaning a solid, monohull ballast-keeler was not easily possible. However, I had other constraints. The boat would not always be ‘elsewhere’. Most of the time it had to be suited to sailing locally on the River Deben. This is a beautiful, rural river on the East Coast of England. These days, most visiting yachtspeople regard it as being very narrow, very shallow and full of parked craft, so they quickly motor up and down it. I wanted to sail up and down and that included tacking through the three major areas of moored craft when circumstances demanded it. This meant that the trimaran I designed should be very manoeuvrable and quick to tack. The river demanded that it should have a shallow draft to traverse the extensive mud flats and also, it must suit my half-tide mooring at the top, where the boat would be aground for much of the time.

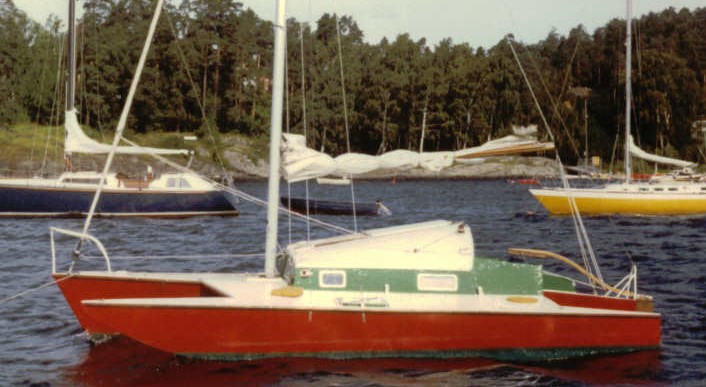

The craft that was eventually built.

Does it look acceptably modern?

It was designed and built many years ago.

Full cruiser

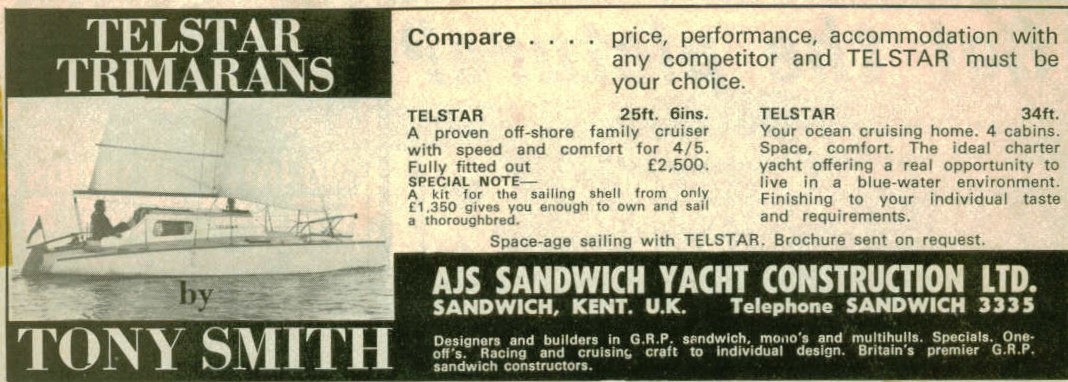

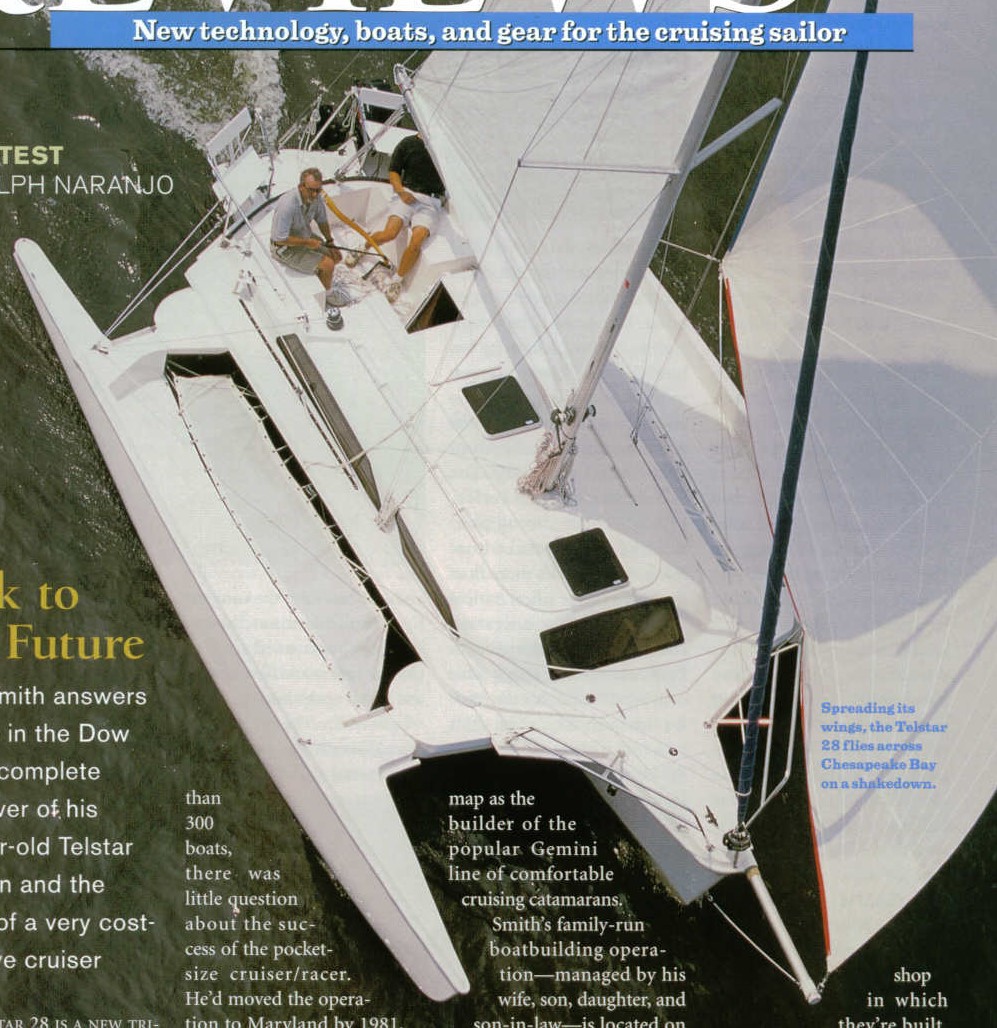

For trailing, the boat would not be much more than 25ft in length. At the time, only one commercially-produced trimaran close to this specification was available and that was the Telstar, designed and produced by Tony Smith in Sandwich in Kent. I call it a ‘Full Cruiser’, because it was not a skinny, stripped-down, racing boat. It could take a family sailing and they could live on board. I wanted a Full Cruiser, as I will describe shortly.

Below. Telstar History.

Top left. Tony's plywood 26ft Endeavour he built in Liverpool and sailed to the East Coast.

The cabin roof has been raised at the back. Laminated tiller added. Picture taken in Norway.

Top Right. Yachts&Yachting advert for first Telstar. Illustrated with one-off boat in foam sandwich built by Tony in a back garden in Ipswich. Not folding.

Bottom Left. From the advertising brochure. Commercial Telstar 26 Mk 2 being produced in Sandwich, Kent. Vertical folding wings.

Bottom Right. From front cover of Cruising World 2003 the updated Telstar 28. Horizontal folding wings

My concept for such a small trimaran is unusual. The main requirement for trimarans is performance and the present-day range of folding boats do deliver this. They are capable of doubling the speed of monohulls of the same length. I was NOT seeking this speed. I wanted the other qualities already mentioned, that can be found in the craft-type. Shallow draught, lighter-than-monohull weight, but I also needed the living space of the Telstar and most unusual, I wanted an inboard-diesel engine. This is a bit of a bombshell to the sailors of small multihulls. Today, trimarans to 30ft will use only a 10hp outboard at the most. Many will use only 6hp. Small trimarans are very weight sensitive. They can only deliver their speed potential if their power/weight ratio is right. Today, we see much bigger rigs on sailing boats of all types. We see better sails and rigs capable of carrying much higher loads. We see lighter, stronger, hull-laminating materials and these things have resulted mainly from experimental efforts and developments in multihulls. We do not see diesels in small trimarans.

Outboard & Inboard

Why put an inboard diesel in a small trimaran? Briefly, I wanted the propellor to be in the water when I needed it. I have been on lightweight boats in rough, choppy, seas and if they have an outboard on the stern then it will be lifted and lowered by the wave action. One minute it can be screaming at high revs in the air and the next it is being plunged into water deep enough to dunk the machine head. If the boat is attempting to enter between the granite walls of a harbour with the tide sluicing across the entrance, then having the propellor in the water, providing reliable drive, is essential for safety. An inboard does not need deploying onto the stern, does not require acrobatics over the transom to lift its weight or refuel it. Weight on the ends of light boats is never good. If the complexities of an outboard well are to be avoided, the only place for an outboard on small multihulls is alongside the mainhull close to the cockpit and this means giving thought to the lift/lowering mechanism, starting it, and protecting it from wave action.

The main drawback to the diesel in a lightweight boat, is weight. The second potential difficulty is fouling a rope around the prop, but that is true for monohulls anyway. My preference was to take the weight penalty in exchange for the reliability of having the thrust when I needed it most. This weight issue basically ruled out conventional trimaran designs at the time of contemplating the build. To get what I needed I had to construct a mainhull wide enough to carry the extra engine weight. The special craft I envisaged might be described as a slightly 'fatter', trimaran and I would be forgoing 'some' of the primary advantage (speed) of the craft type, by building it. The weight penalty is not immense. Outboards, their fuel and controls are not weightless. Subtract this weight from that of the diesel installation and the difference might only be like taking a extra, young passenger aboard, something commonly done on cruising boats. Early cruising catamarans used outboards, but then eventually moved over to fit two diesel engines, one in each hull. It didn't destroy their performance, it improved their manoeuvrability in harbour and it enhanced their popularity - because they were designed for the additional load. Electric engines and their batteries are a current option, but this craft now has a modern 14hp inboard which gives confidence in its ability to move it reassuringly against wind and tide if that should be necessary.

The Way it sails

It might be questioned; what would be the point of building a trimaran without the very high speed usually associated with these craft? My answer is - the way it sails. It is the quality of movement that the trimaran produces. Trimarans are float-stabilised monohulls, that is, they move and behave in similar ways to monohulls. When a gust of wind strikes the sails, both types heel over and then recover their attitude. The catamaran is a much stiffer craft. It does not heel in the same way. It remains solid and unyielding as it moves forward. Its action does not feed the wind variations to the helmsperson in the same way as the tri and mono. Trimarans are very stiff monohulls. When working to windward this constant feedback of fluctuating heel angles delivers the information to the helm even though it is a more subtle message than that received on the monohull. It is light and responsive. People sailing the trimaran for the first time say it feels like a dinghy.

Monohull sailors will say that their boats are better to windward, but whilst this may be true, it is marginal now. On my river, almost no other comparable craft has produced a better windward performance than the little cruiser that is being described here. When the wind is on the nose, the performance of this trimaran is roughly equal to most well-sailed monohulls; off the wind the trimaran is supreme. Good catamaran cruisers could equal it off the wind, but in this small size it is not easy to produce internal standing headroom, which  was an essential choice for me. The Hirondelle, Tiki and Strider designs were the cruising catamarans available when I designed my cruiser. There were self-build plans for others including Wharram, Brown and Woods.

was an essential choice for me. The Hirondelle, Tiki and Strider designs were the cruising catamarans available when I designed my cruiser. There were self-build plans for others including Wharram, Brown and Woods.

Wharram Tiki 26

The trimaran has the ability to quick tack that the similar-sized catamarans did not possess. This is because as a float-stabilised monohull it lifts its floats clear of the water as it tacks. Only the single, central hull is being steered around. The catamaran has two immersed hulls describing circles of different radii in the water. In a road vehicle it took the Ackermann linkage to make this possible with the wheels, but this can’t be done on a catamaran. Their strong points for cruising are space and stability, especially when the bridge-deck becomes high enough for standing headroom, but that was challenging in this size. When they are large enough to have an engine in either hull to give them manoeuvrability, they become the perfect family accommodation – as is being proven by the charter market.

The best small yacht in the world

The best small yacht in the world

I had my boat sketched out in my mind. Trailable, demountable, 25ft length, manoeuvrable, shallow draft, inboard diesel and I added ‘full cruiser’ to carry the full cruising load for two adults and two children. I have called it the Westerly Centaur-of-trimarans: a solid performer, well respected and a secure sailing craft. I recently found this image of the Centaur on the internet under the heading of: The best small yacht in the world. on Dylan White's KTL website. He says '26ft and 4 tonnes. Small enough to single-hand and big enough to take the rough stuff. A Centaur could handle almost anything the British weather could throw at it. The space below is genius.'. At the time that I was planning my boat I wanted it to be, 'The finest estuary cruiser in the world'. My boat may not be everyone’s choice, including some trimariners, but it had merits for what I wanted it to do, sailing the East Coast rivers and possibly, possibly, going ‘elsewhere’. All that now remained was to work out the details of the hulls, crossbeams, cabins, accommodation, cockpit, engine, rudder, boards, fixtures, rig, sails and equipment. Actually, I haven't yet seen anything that I would prefer, that covers all the functions as well as she does - for me, so maybe I wasn't too far short of my ambitions?

I am about to relate the choices I made in the boat's construction in the hope that something that I say may be of use to you the reader. I do not expect that anyone will build a boat exactly like this, but some aspects of the construction may be useful. The boat was made on a flat table, as described on this website.

Before starting

Just in case you may be contemplating building - If you have not built a substantial craft on a budget before – a few words for consideration. The most important quality that you will need is endurance. It is going to take longer than people think and most of the work is just very tedious. Do not set false deadlines such as: It must be finished by xxxx date. Even more important, do not announce any date to the wider world, because it will put you under pressure. If anyone wants to know – It will take - as long as it takes. Watch the house-build/conversion programmes on TV. How many of them run over time and over budget? How much stress does it cause? Houses can be relatively simple compared to the intricacies of a boat and house materials are so cheap compared to anything with ‘marine’ written on it. It is going to cost more than you think, so spread it over time. The job is hard enough without people constantly asking, ‘Are we nearly there yet?’

AND ...

You need somewhere to build it that is relatively close to home. Having long journeys adds hugely to the time it will take. It is more accurate to say that precious, boatbuilding time will be lost when travelling. If you are building in your garden, remember that the process is very dirty with dust and smell. Machinery like grinders, make noise. If you are building temporary shelters you may need more than one and the time it takes to build them. You will need quite a bit of storage space for rolls of glass and polythene, drums of resin, sheets of ply etc. I built Starship at home in a garden the same length as the boat and could step out of my living room window into the boat. I determined not to subject my family to this 5year ordeal again, for this boat. I advertised in the local newspapers asking for an unused barn. It had to have water, electricity and security. Living in a rural area, I was lucky to find a suitable building. I built a polythene shelter inside the barn for the construction of this boat. My friend Paul Brown (see GRP flat table) accessed an old portable building for the construction of his catamaran Wakey Wakey in his back garden.

There are some circumstances that could shipwreck your project. If you are building inside polythene shelters in your garden, be advised that they are not regarded by other people as being ‘beautiful'. Some people will take a strong exception to the smell of polyester resin. If there was determined opposition from neighbours it would be difficult to complete the job. During the Starship build I hadn’t calculated for neighbours changing, nor allowed for the powerful influence of visiting friends and relatives upon those neighbours, by questioning what could be happening behind the flapping polyethene they could see from their windows. The best defence The boat emerging from the building barn of any project is communication and information. When people can The original colour scheme was later changed see what is happening, they appreciate the effort involved and their attitudes are modified. They may even begin to feel some involvement, by periodically being included with such an exciting project.

There are some circumstances that could shipwreck your project. If you are building inside polythene shelters in your garden, be advised that they are not regarded by other people as being ‘beautiful'. Some people will take a strong exception to the smell of polyester resin. If there was determined opposition from neighbours it would be difficult to complete the job. During the Starship build I hadn’t calculated for neighbours changing, nor allowed for the powerful influence of visiting friends and relatives upon those neighbours, by questioning what could be happening behind the flapping polyethene they could see from their windows. The best defence The boat emerging from the building barn of any project is communication and information. When people can The original colour scheme was later changed see what is happening, they appreciate the effort involved and their attitudes are modified. They may even begin to feel some involvement, by periodically being included with such an exciting project.

AND ...

During the construction of Starship I began to note an irritating itch around my wrists, then my neck. The itching spread to my forehead and shoulders and face. My skin burned, just like severe sunburn. My lips began to split and the skin to flake away. After some time, the doctor advised that I had an allergy to something like an adhesive, but it wasn’t that. I experimented by loosely bandaging a shaving of teak, that I was using for fitting out, to the inside of my forearm for a couple of hours. Next day I had a blister where the shaving had been. Teak is a wonderful timber for marine work, but it has evolved to be toxic, to protect itself from insect and fungal attack in its natural environment. It also protected itself from me. To work with it, I had to be outside, fully kitted out with gloves, balaclava, face mask, sealed cuffs and neck. If my allergic reaction had been to polyester resin or epoxy it would have been impossible to have built the boat. I had worked with wood all of my life and had never experienced problems like this before, so it is better to be sure before embarking on anything expensive.

Anyone contemplating a big construction would be well advised to seek contact with the materials to be used on several occasions prior to starting the work. I understand that there could possibly be no adverse reaction on the first contact, which only serves to sensitize the body. The real trouble can only be revealed on second and third contact.

In addition to the boat

In addition to the boat

Trailer

To make a trailer-sailer, a trailer is needed and during the constructioin of the boat I was fortunate in finding one locally in the small ads. It had been used for a powerboat, but by cutting off the many rollers I had a flat, twin axle trailer with winch. I blocked the keel a little higher and using 25mm ply encapsulated in glassfibre, I fabricated some holders for the hulls. I achieved the shapes by laying up pad of glass onto carpet taped to the hulls in the appropriate places (below left). I wanted non-scratch surfaces on the pads. I was later to regret the carpet, as when it got wet with rain water it retained and held the moisture against the hull and began to damage it. It is better to have a non-absorbent material for the pad and to only insert carpet for travelling. A shaped moulding was made to secure the bow of the boat. Some square metal tubes with padded  tops were fabricated to make legs (above right) to support the mainhull under the beam shelves. These legs could pivot and were locked upright with a couple of bolts through the support holders. The lower component of the support legs slides into the square tube of the trailer.

tops were fabricated to make legs (above right) to support the mainhull under the beam shelves. These legs could pivot and were locked upright with a couple of bolts through the support holders. The lower component of the support legs slides into the square tube of the trailer.

Demountable not folding

To move the floats up and down for assembly, they are suspended with webbing straps from the aluminium poles that are part of the crossbeam structure. The support arms are lowered during the movement and then lifted again to support the mainhull. A webbing ratchet strap linking crossbeam to trailer can be applied to the opposite side of the boat to help to secure it in an upright position during the movements (see the section on Floats).

To move the floats up and down for assembly, they are suspended with webbing straps from the aluminium poles that are part of the crossbeam structure. The support arms are lowered during the movement and then lifted again to support the mainhull. A webbing ratchet strap linking crossbeam to trailer can be applied to the opposite side of the boat to help to secure it in an upright position during the movements (see the section on Floats).

With the broad brush strokes in place I will move on to look at my considerations for the mainhull, the floats and beams, the development of the rig and then the arrangement of the interior of my Estuary Cruiser.