GRP Estuary Cruiser

The Swing Rig

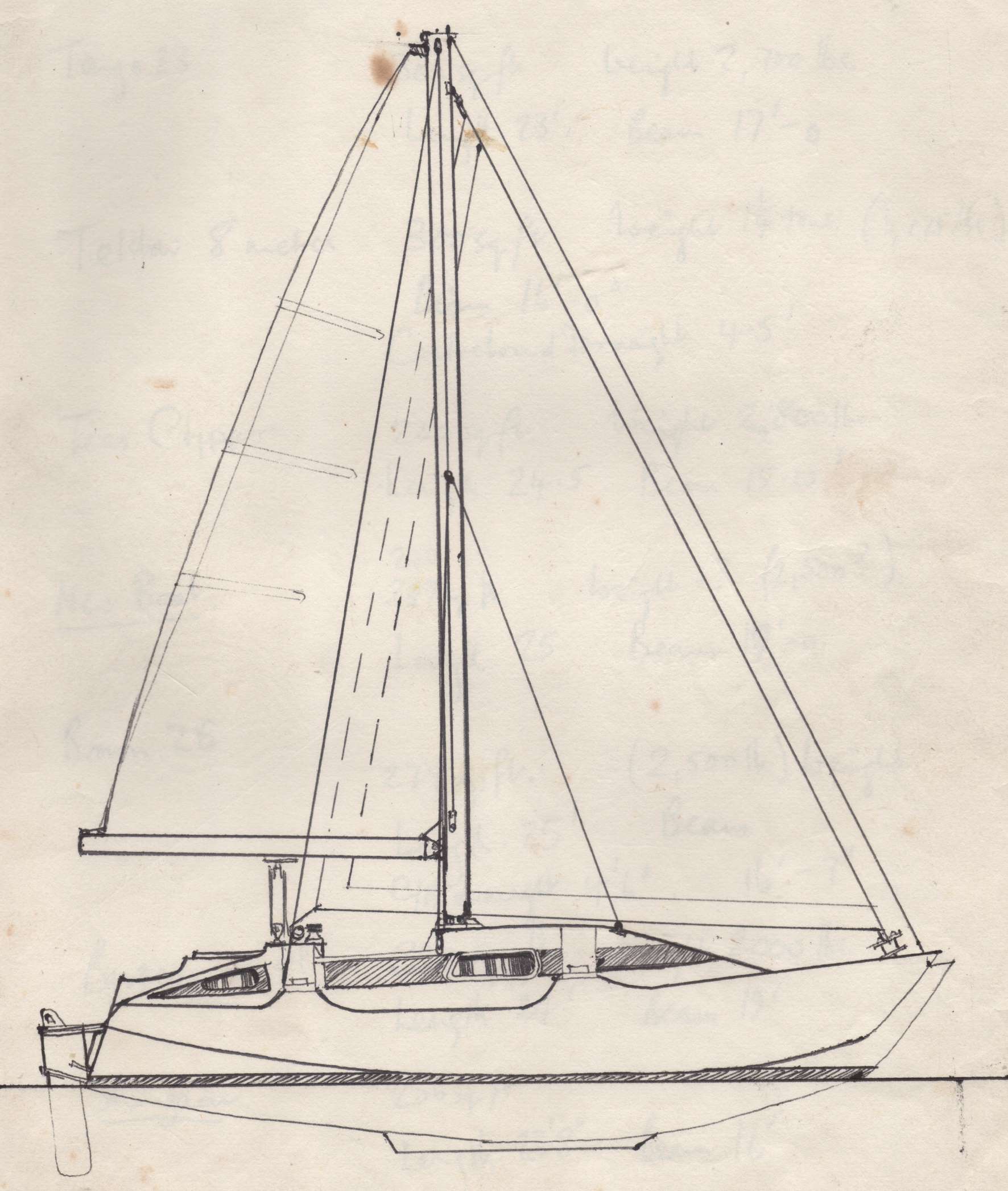

When I started thinking about the boat, I had in mind to try to use the Prout rig found on most of their catamarans. I made scale drawings that provided quite a generous sail area, quite low down to limit heeling forces. Basically, with this rig, the mast is stepped well back on the hull and there is a small mainsail. The majority of the power comes from the genoa which is oversized. Its angled luff delivers an upward drive that minimises depressing the  bows.

bows.  A roller genoa is an easy sail to set and to remove; it is just a matter of winding the reefing line. Having the mast well back on the boat and just in front of the cockpit means that all the sail controls are immediately to hand without having to go forward, or alternatively, lead many lines back across the deck to the cockpit. The only major drawback is having to winch in a big sail on either tack when beating in the confined space of a river. The answer to this would be to reef the sail, but then the boat would not to be sailing at full power. In more open sea conditions this would be less of a disadvantage. Modern racing trimarans all set the mast well back to use the buoyant lift of the hulls forward to counteract any depressive drive from the sail plan. It is a good system. Early concept sketch

A roller genoa is an easy sail to set and to remove; it is just a matter of winding the reefing line. Having the mast well back on the boat and just in front of the cockpit means that all the sail controls are immediately to hand without having to go forward, or alternatively, lead many lines back across the deck to the cockpit. The only major drawback is having to winch in a big sail on either tack when beating in the confined space of a river. The answer to this would be to reef the sail, but then the boat would not to be sailing at full power. In more open sea conditions this would be less of a disadvantage. Modern racing trimarans all set the mast well back to use the buoyant lift of the hulls forward to counteract any depressive drive from the sail plan. It is a good system. Early concept sketch

Sails in General

Original Telstar 285 sq ft Weight 3,175lbs Length 26-3 Beam 15-0

Telstar 8m 300sq ft Weight 3,175lbs Length 26-3 Beam 16-0

Tango 23 300 sq ft Weight 1,800lbs Length 23 Beam 19-0

Brown 25 274 sq ft Weight 2,500lbs Length 25 Beam 16-7

Tees Clipper 220 sq ft Weight 2,800lbs Length 24-6 Beam 15-25

Shangaan 256 sq ft Weight 3,175lbs Length 23-8 Beam 16-0

Buccaneer 24 320 sq ft Weight 2,000lbs Length 24 Beam 19-0

My Boat 270 sq ft Weight 3,000bs Length 25 Beam 18-0

Sail Area – Weight/Length

Sailing performance can be visualised in its simplest terms by thinking of the Power/Weight ration. How much power is trying to drive

what weight forwards? I gathered information from sales leaflets to compare them. The length and the beam of the boat are also

important, especially beam, which can determine stiffness. Stiffness determines roughly how much power can be extracted from the

wind. The sail area will give an idea of how much power can be gathered from the wind.

The Telstars are commercial cruising craft moulded in GRP with solid wingdecks. The others a ply/epoxy which is much lighter, but

less durable. Tango 23 was a Kelsall design with more beam, less weight and more sail area than the Telstars. I believe it won the

Round the Island Race one year. Jim Brown’s 25 was a self-build design and unusual in that it had a centre cockpit. It was

Round the Island Race one year. Jim Brown’s 25 was a self-build design and unusual in that it had a centre cockpit. It was

promoted as an ocean-crossing craft. The suggested weight would probably need skilfull, weight-saving construction to be

achieved? James Wharram always used to complain of published weights, which he maintained were usually ‘notional’ and

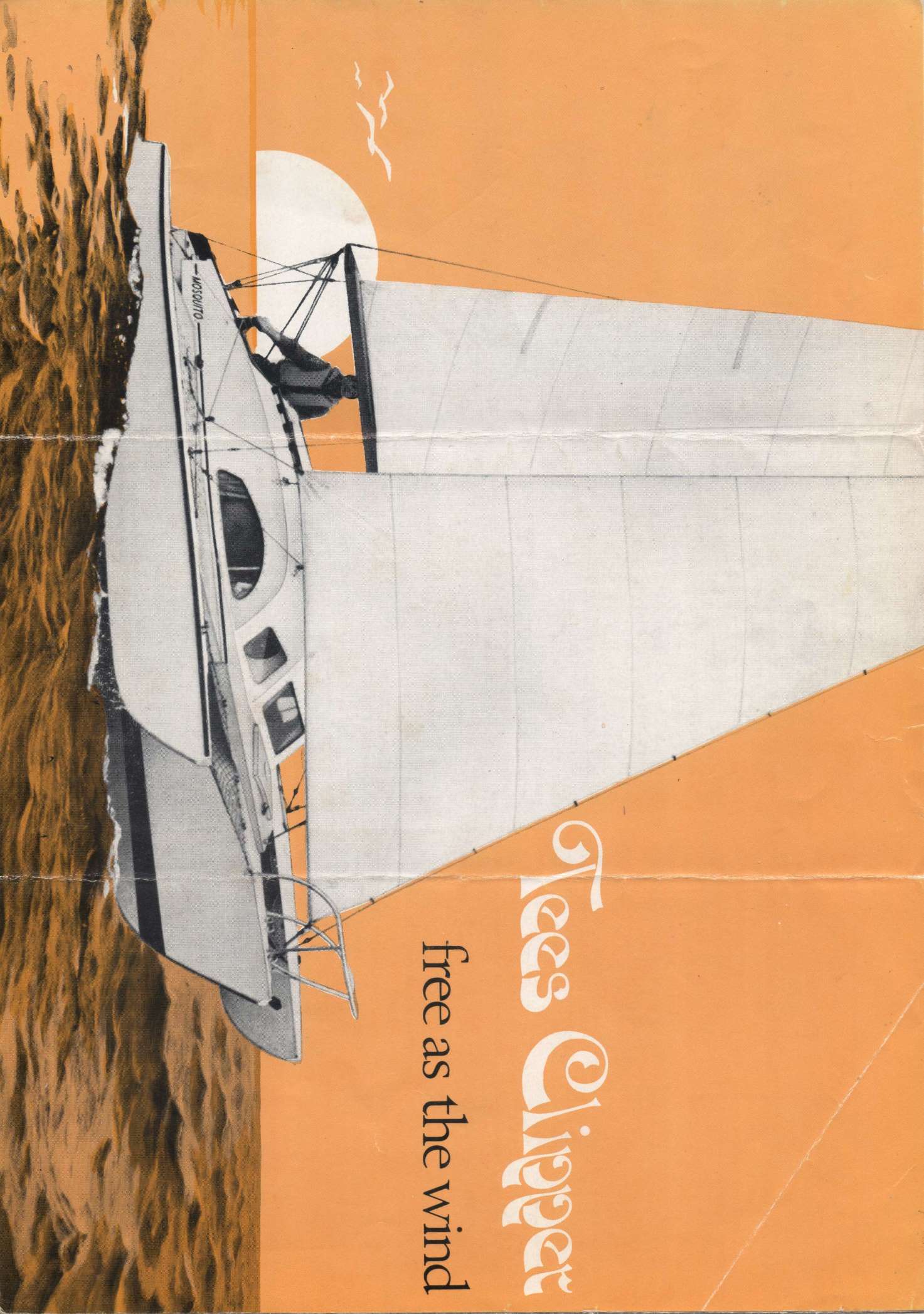

under-estimates. Tees Clipper (right) didn’t make it into volume production; possibly it was a one-off? Shangaan was the

smallest Simpson-Wilde design. They constructed a number of medium-sized trimarans used for racing and possibly

they were under-floated as there were incidents concerning them, probably being pushed too hard. They had an appealing appearance. I sailed on a couple of

them, including Shangaan. The Buccaneer 24 was a Lock Crowther design. He was a very successful designer of racing multihulls in Australia. I

delivered one to The Netherlands and it sailed wonderfully. I described it as ‘thistledown’ it was so light and responsive.

delivered one to The Netherlands and it sailed wonderfully. I described it as ‘thistledown’ it was so light and responsive.

Its performance was that of the ‘classic’ lightweight trimaran that is a joy to experience. Its performance would probably

still be relevant today. It was not a weight-carrier.

These were the boats of the time. The engineered, folding, trimarans of today were only just on the horizon in Europe.

They grew from the original, wooden, Trailer-tri designed by New Zealander, Ian Farrier.

Above. A Simpson-Wilde design

The magazine article

I continued with this intention of using the 'Prout' rig and even acquired a mast for it, until I read an article in Yachts and Yachting magazine by Jeremy Atkins entitled The Swing Rig. It explained about the evolutions of a rig concept by Roger Stollery. In the article a number of boats were mentioned Mirror, Marblehead, Bembridge Redwing, Punch dinghy and the latter craft was linked to the Waldringfield Sailing Club which is on the River Deben where I sail. It listed a number of advantages of the rig which included:

- It imposes less bending force on the mast and so a smaller section can be used

- Jib and main are controlled by a single sheet

- No requirement for a kicking strap and reduced sail twist

- Improves slot-effect of the self-tacking jib on all points of sail

- Sails as well as conventional Bermudan rig on all points, but increases off-wind performance

There was also a companion article on the Punch dinghy which had roughly the same dimensions as the Mirror 11 and the conclusion was that the boat, which had a number of innovative features, did sail well. The boat had originally been designed for a lady called Judy, hence the name.

I was impressed by the innovation as much as anything, but also it seemed that with the local link I could investigate further – and so I did. I contacted Roger Stollery and through correspondence and in meetings with him I decided to give the rig a trial. Roger clearly knew what he was talking about and had approached the rig development in a logical, dispassionate way to arrive at the conclusions he had reached. His experiments had gone much further than the magazine article had covered and he had several, much more sophisticated rig improvements beyond those reported. It took me a little while to appreciate that I had missed the significance of the word ‘Marblehead’ in the magazine's list of boats as I wasn’t aware of this class of craft. To give the craft its full title, as mentioned in the article, Radio Marblehead ‘Pickaxe’. It was a model yacht. Roger was an expert in model yachts, but he had proved in the photographs in the article, that the rig could be effective on larger craft. There is no crew aboard a model yacht other than the radio control, so the craft has to use a predictable, balanced rig and it has to prove itself in some very competitive racing situations. I liked the rig, because at a quick glance it looked almost Bermudan and could probably be used on my boat.

What is the Swing Rig?

Well basically, there is a single boom that extends in front of, as well as behind the mast. The mainsail attaches to the boom in the normal way, but the jib is also attached to it. The jib tack does not fasten to the bow of the boat, but to the front of the extended boom. What difference does this make? The rig uses the jib as a balancing area to the power of the main. It is like having a balanced rudder. The smaller area forward of the pivoting axis generates some power to counteract the greater force of the area behind that axis. It is like a see-saw. If a person sits on one end and another person tries to depress the opposite end by hand, it will be difficult. If some weight is placed on the see-saw towards that lighter end, to help counterbalance the seated person, then it will be easier to depress the light end by hand. With a normal rig, as the mainsail gybes, it is rushing out and must be controlled by the main sheet. With a Swing Rig, as the main is rushing OUT, the jib is rushing IN, against the wind pressure and acting as a brake on the main. It is mainly about the balance of forces.

The Slot Effect

It is also about the slot effect and this is hugely important, for this is the basis of the rig’s superior quality. In simple terms, when sailing, the jib catches the wind and deflects it onto the mainsail. The air is compressed through the gap (slot) between the two sails and speeds up as it does so. This increases the effectiveness of the airflow onto the main.

When adjusting sails for bearing away from being close-hauled on a ‘normal’ rig, both sheets are eased, but the gap between the leach of the jib and the main gets bigger. It no longer funnels air onto the main in the same way and the jib clew begins to lift allowing the sail to twist. The top of the sail turns away from the wind and loses much of its effectiveness. The Swing-rig jib doesn’t do this. It stays in constant relationship with the main and it is automatically poled-out to windward as the sails are eased, so that it is always in clean air, working. This is particularly the case when approaching a run. The conventional jib in a ‘normal’ rig disappears behind the main and is blanketed. It lifts and flaps ineffectively and it is hard work to get any appreciable drive from it, unless it can be goose-winged. The Swing rig jib continues to drive and provides a counterbalancing force to all the sail power being delivered onto one side of the craft by the main alone. It is automatically poled out to goosewing on the run.

Self-Tacking

And there’s more! The jib is self-tacking across the boom, so there is no need to change jib sheets on winches and crank the handle after every tack, which greatly improves handling in the confines of a narrow river with moored craft. Whilst it may seem that the concept is very new, this isn’t quite the case. A balanced lugsail has a section forward of the mast which as its name says, has a similar balancing effect. Junk and lateen sails also use the principle, but without the same slot effect. In the Swing rig the two sails must have proportional sail areas, such that the jib is approximately one third of the area of the main. I found that the jib could be a bit bigger than this. To re-apportion the sail areas from my originally-intended Prout rig, I had to have a taller mast.

Aero rig

Many years later, Practical Boat Owner magazine contained articles on a similar rig, which by that time had become known as the Aero rig made by Carbospars. It was like the Swing Rig, but Aero rigs used a carbon fibre, unstayed  mast. By that time, I had already worked out my version of the rig and my mast was stayed, so that I could revert to a conventional rig if I needed to, by removing the forward section of the boom. As my boat is a trimaran, my rig also had to be instrumental in lifting the windward outrigger/float as the boat heels, so the cap shrouds had to do this. The PBO article was entitled The Rig of the Future? And the rotating mast and boom were a locked, single unit with the foot of the mast passing through the deck and pivoting on a heel fitting on the keel (if used in a monohull). The article identified one problem with the rig stating that the jib could not be backed, but said that ‘if necessary – devise some lash-up for heaving-to’, a manoeuvre which involves backing the jib. I had already addressed this problem, but for a different reason and I wouldn’t call it a lash-up. My solution is so effective that several visitors have singled it out as the most useful device on board. More of this later, as I shall explain it when I look at my rig. The commercial carbon-fibre rig was not cheap. This article by the Consulting Editor, Denny Desouter, concluded, ‘I am convinced that many owners will think that the merits of the rig are worth the money. It is when one experiences it for oneself that one is convinced.’

mast. By that time, I had already worked out my version of the rig and my mast was stayed, so that I could revert to a conventional rig if I needed to, by removing the forward section of the boom. As my boat is a trimaran, my rig also had to be instrumental in lifting the windward outrigger/float as the boat heels, so the cap shrouds had to do this. The PBO article was entitled The Rig of the Future? And the rotating mast and boom were a locked, single unit with the foot of the mast passing through the deck and pivoting on a heel fitting on the keel (if used in a monohull). The article identified one problem with the rig stating that the jib could not be backed, but said that ‘if necessary – devise some lash-up for heaving-to’, a manoeuvre which involves backing the jib. I had already addressed this problem, but for a different reason and I wouldn’t call it a lash-up. My solution is so effective that several visitors have singled it out as the most useful device on board. More of this later, as I shall explain it when I look at my rig. The commercial carbon-fibre rig was not cheap. This article by the Consulting Editor, Denny Desouter, concluded, ‘I am convinced that many owners will think that the merits of the rig are worth the money. It is when one experiences it for oneself that one is convinced.’

The magazine article description of the rig (See Yachting World photo above) was prompted because in the same issue there was an evaluation of the updated Hirondelle Family catamaran cruiser being constructed by David Trotter of Swallow Yachts. This 23ft catamaran originally designed at 22ft by Chris Hammond was formerly the most successful, commercial cat-cruiser in this size range with over 300 being built. The article compared the performance of one craft using a conventional rig with another similar one, using the Aero rig. The more-expensive Aero rig had the ability for the mast to flex away at the top under a heavy wind gust. The figures given were of interest. The mast ‘tip could deflect almost 20inches in a Force 4 wind and a 45knot gust (Force 9) with all sails set will curve it by around 6’-6”.’ This was mentioned as a safety feature. The Aero rig also had the ability to rotate the total sail plan 360°. My fixed aluminium mast does not rotate and the sail plan swinging around it only moves through the conventional arcs associated with the accepted Bermudan rig.

In one respect my rig is more like the Aero rig than the accepted Swing rig design and that is in the securing of the foot of the jib. On the Swing rig the foot of the jib is attached to a ‘floating’ spar, not directly to the boom. The spar is attached to the forward boom, one third of the way back from the front of the spar. This applies the one-third balancing rule to the jib itself, as it, in its turn is applying the one-third rule to the main. I found this feature near impossible to arrange and so, I had evolved virtually the same arrangement as was later used on the Aero rig which was to secure the jib tack directly to the boom and not to use another spar. More of this later. Dave Greenwell who wrote the craft review concluded that he saw merit in both systems, conventional and Aero rig. He would probably choose ‘the Aero rig for cruising in developed parts of the world’, but would ‘take the traditional rig for more remote parts.’ He was probably being cautious about replacing the flexible carbon mast.

Performance comparisons

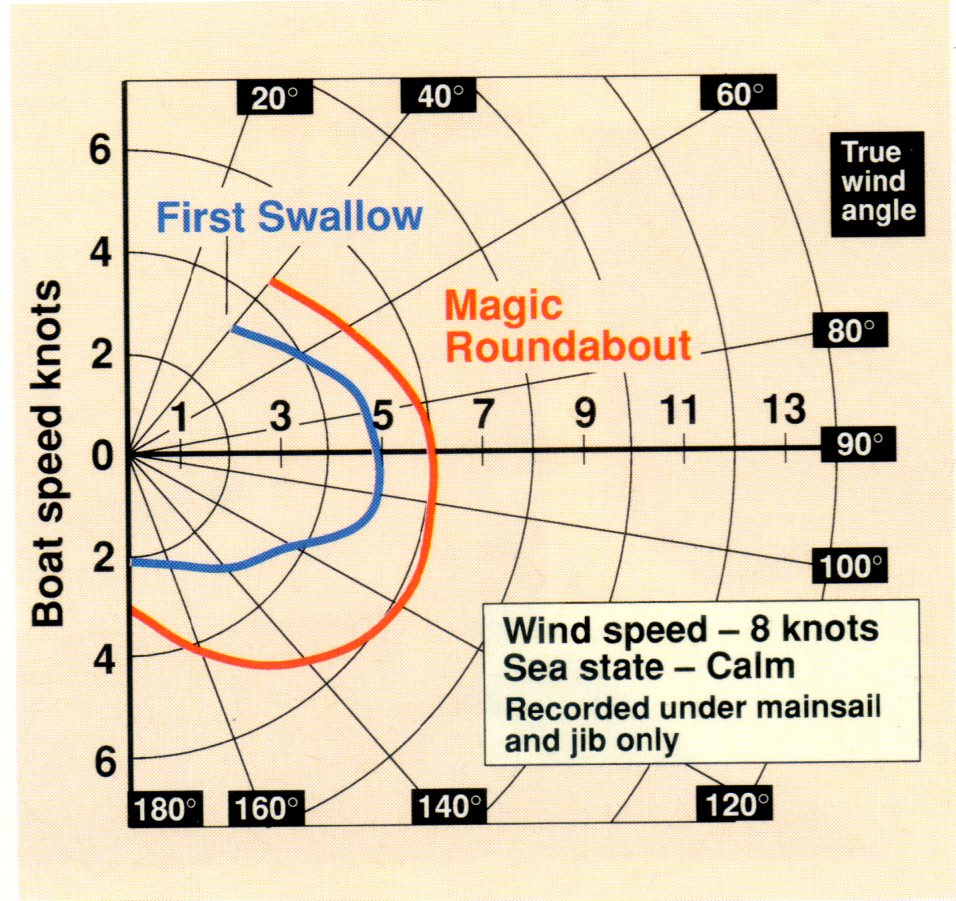

At about the same time as the PBO boat test, Yachting World published articles on the same two Hirondelle Family catamarans entitled ‘Swings and Roundabouts’. The article by Matthew Sheahan included polar diagrams (see right) recorded on their computerised data-logging system of the boats sailing in 8knots of wind off Weymouth.

At about the same time as the PBO boat test, Yachting World published articles on the same two Hirondelle Family catamarans entitled ‘Swings and Roundabouts’. The article by Matthew Sheahan included polar diagrams (see right) recorded on their computerised data-logging system of the boats sailing in 8knots of wind off Weymouth.

The conventional craft First Swallow (blue line) had a sail area of 245 sq. ft and the Aero rigged Magic Roundabout (red line) a smaller sail area of 212 sq. ft. Diagram from Yachting World

The polar diagram showed the Aero rig to be almost a knot faster on all points of sail and sometimes more than this especially on off-wind courses.

Bigger Rigs

The aero-style rig has been experimented with for racing. Most notable was the huge 60ft French racing catamaran Elf Aquitaine II which crossed the finish line in second place in the 1984 Trans-Atlantic Singlehanded Race skippered by Marc Pajot. The aluminium boom is called a ‘balestron’ in France, meaning sprit or spar. The  rotating wingmast alone had an area of 409sq.ft. and was set on roller bearings at the base. The mast had standing rigging. This boat turned up again in 1989 to win the Round Britain Race, but this time called Saab Turbo. Cruising craft both cat and mono up to the 60ft range have used the rig (see left) doing tens of thousands of miles and designers, ancient - such as Manfred Curry and Nat Herreshoff, as well as modern, such as Uffa Fox, Dick Newick, Derek Kelsall, Van de Stadt, Darren Newton, Kurt Hughes or John Shuttleworth have recommended it for use on their craft.

rotating wingmast alone had an area of 409sq.ft. and was set on roller bearings at the base. The mast had standing rigging. This boat turned up again in 1989 to win the Round Britain Race, but this time called Saab Turbo. Cruising craft both cat and mono up to the 60ft range have used the rig (see left) doing tens of thousands of miles and designers, ancient - such as Manfred Curry and Nat Herreshoff, as well as modern, such as Uffa Fox, Dick Newick, Derek Kelsall, Van de Stadt, Darren Newton, Kurt Hughes or John Shuttleworth have recommended it for use on their craft.

What did I do? See the next article.